Famous Dublin Actress Eilin O’Dea as Molly Bloom

Eilin Odea as Molly Bloom bears her soul on life, love, sex and lonliness in James Joyce’s Ulysses

Click Here for INL News Amazon Best Seller Books

Click Here For INL News Corporation Cheap Domains and Cheap Web Hosting

Click Here For INL News Corporation Cheap Domains and Cheap Web Hosting

Click Here For INL News Corporation Cheap Domains and Cheap Web Hosting

Click Here for INL News Amazon Best Seller Books

Click Here for the best range of Amazon Computers

Click Here for INL News Amazon Best Seller Books

Click Here For INL News Corporation Cheap Domains and Cheap Web Hosting

Amazon Electronics – Portable Projectors

Famous Dublin Actress Eilin O’Dea as Molly Bloom

Famous Dublin Actress Eilin O’Dea as Molly Bloom

She struts out on stage as the lights come up, affecting a smooth, liquid gait while absently kicking aside a stray bit of clothing from her path. Leaning like a cabaret singer on an iron bedpost, a gold scarf wrapped loosely around her neck, she presents us with a warbling love song, accompanied by the ghostly strains of an accordion. Self-satisfied and seemingly more comfortable in her body than most, this is Eilín O’Dea’s embodiment of Molly Bloom, lifted from the pages of the ‘Penelope’ episode of Joyce’s Ulysses.

The episode depicts a sleepless Molly Bloom in the early morning of June 17, 1904, unable to turn her mind off as she meditates on sex, death, bodily pleasure and abjection, and her complicated marriage to Leopold Bloom, the central character of Ulysses. On the page this episode reads like an unedited transcript, writing that offers a linear representation of the simultaneity of thought, the echo chamber of the mind. For roughly 20,000 words there is hardly a punctuation mark cordoning off cogitation, allowing porous boundaries between separate images and lines of thought to clash, merge and then part ways again.

Molly Bloom

The New York International Theatre Festival Presents

Irish Actress Eilin O’Dea in Her One-Woman Performance

of the Famous Soliloquy from Ulysses

DIRECTED BY LIAM CARNEY

ABOUT THE PERFORMANCE

“Absolute artistic genius…”

— USA Weekly News

Date: 19th January – 23rd February, 2008

Time: 8:30 P.M.

Venue: Bleeker Street Theatres

45 Bleeker Street

New York, NY 10012

Molly Bloom’s monologue at the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses is recognised as one of the most famous female narratives in modern literature. It has been used as the basis of songs, re-appeared in movies, quoted in other literary works and in terms of its effect on Irish culture was, as the award-winning writer Eavan Boland puts it, “a liberating signpost to this country’s future.” Sensuous, compelling and at times hugely funny, this soliloquy is the only time in Joyce’s seminal novel where Molly’s voice is heard directly. In it, we hear the otherwise silent character bare her soul on life, love, sex, and loneliness. A must-see for fans of James Joyce, literature and independent women everywhere!

Eilín O’Dea has tamed Molly’s tumbling consciousness with a rather straightforward, naturalistic performance that is nonetheless rich, passionate and compelling. This is a performer’s showcase (no director or designers are credited) and O’Dea, with charismatic ease, makes the most of it. Clad only in a shift so loose it seems to stay on by a sheer act of will, Molly Bloom takes us through a meandering narrative that tours the length and breadth of her life, from her sexual coming of age in Gibraltar, to her extramarital romantic conquests, to her contentious relationship with her only daughter, to the conflicting nature of her life with Leopold. O’Dea hardly shies away from embodying the manifestations of physical desire and discomfort that Molly describes to us. Feeling the onset of her period and plagued by gas, O’Dea’s Molly hikes up her shift and squats squarely on her chamber pot, admiring the soft, sensual whiteness of her thighs as the indifferent cycle of human waste takes it course. It is, for all the suggested abjection, a beautifully achieved moment both in Joyce’s text and O’Dea’s performance, a reminder of the body at seeming cross-purposes, at once indifferent to human desire and spurring it on, the fusion of the vitality of sex and the slow churn of digested death.

Given the ease with which O’Dea’s Molly comports herself in the intimate setting of Molly’s bedroom, it’s possible to forget momentarily that what she reports is not an open airing of personal desire and disappointment, but rather the whirring of a mind hidden away by a potentially more staid public persona. While by all accounts Molly is no shrinking violet in public life, it’s more than likely that what is voiced to the audience would never be voiced entirely to the people populating Molly’s world. This suggests, poignantly, that what is voiced and staged here marks the truth of what Molly, or indeed any of us, will never fully realise in the harsh light of the morning: a life, with all its possibilities, fully lived.

Jesse Weaver – http://itmarchive.ie/web/Reviews/Current/Molly-Bloom.aspx.html

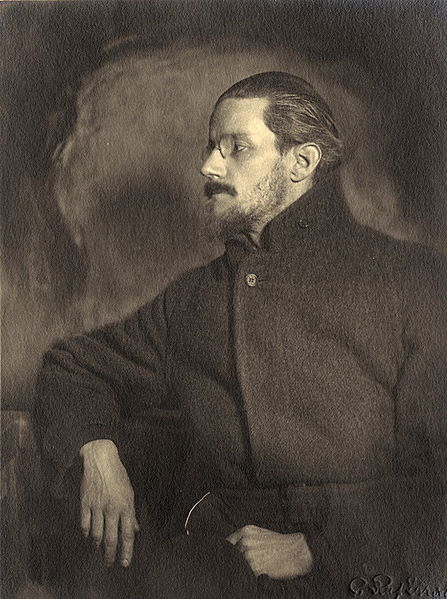

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (1882-1941)

Famous Dublin Actress Eilin O’Dea as Molly Bloom

Eilin Odea as Molly Bloom bears her soul on life, love, sex and lonliness in James Joyce’s Ulysses

Performed at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival

“Wildly funny” **** – Views from the Gods.

http://www.naomihefter.co.uk/the-comedian.html

Stand-up comedy has led Naomi Hefta to do various modelling jobs, writing for other comedians and TV appearances including a documentary all about Naomi herself for Channel 4. Now taking a step away from the stand-up world, Naomi Hefta is happily married and a full-time writer. COMPETITIONS Semi-finalist – LETCHWORTH ARTS CENTRE COMEDIAN OF THE YEAR

Naomi’s well-spoken “posh” persona and glamorous appearance leave audiences surprised and thoroughly entertained when she shares her outrageous stories on the stage. Her passion, for physical comedy in particular, naturally gives Naomi a unique style of delivery and with her striking persona, Naomi has an instant unique selling point which leaves her to be very memorable. Naomi’s influences are Rick Mayall for his brilliant facial expressions, Russell Brand for his unique story telling, Joanna Lumley for her daring and fabulous comic timing and Phil Nichol for his absurdity. Receiving a 4 star review for her debut solo show at the Edinburgh festival 2013, and a 4 star for her second show in for Camden Fringe festival 2015 she interacted and played with her audience whilst literally shocking them with her true stories that are almost unbelievable….Along with outrageous and unexpected stories about love, life and past jobs as a receptionist, she is also able to build a relationship with the audience as she opens up about relatable experiences about mental health. Naomi suffered from depression throughout 2009, 10 and 11 and was diagnosed with PTSD in 2011. This brave decision to show true vulnerability makes her instantly likeable.

Stand up comedy has led her to do various modelling jobs, writing for other comedians and TV appearances including a documentary all about Naomi herself for Channel 4. Now taking a step away from the stand up world, she is happily married and a full time writer.

Joanne TremarcoMore about Joanne

Joanne Tremarco has been making solo shows for the past 6 years. Touring in USA, Uk and Europe. She makes her shows about taboos taking audiences into the unknown with lightness and depth in equal measure. She works with the taboo’s of Sex and death and alongside her work as a fool and an artist she is training to be a doula of Death and Birth. She runs an off shoot Fool’s company with her husband Christopher Murray called FoolSize Theatre which incorporates Street Theatre. Additionally she paints for pleasure and pupeteers for payment ( and pleasure). She has received Arts Council funding on to occassions to support her work. Her current research explores how the twin relationship found in the structure corresponds with the twin relationship of a lucid dreamer and how these may help in the preparation for and the process of death. She also worked with Jonathan Kay and others on Richard II during a 3 year process

2011 Edinburgh Fringe Festival

Forbidden ….. Comically tragic and tragically discovery play in search of intimacy, please and connection..

Enjoy the ridiculousness of the best worst kept secret and of disconnected egos rubbing themselves up.

This is a Fool’s show by Joanne Tremarco and is suitable for all adults…

Joanne Tremarco and Chris Murray from the Nomadic Academy of Fools, an odd-ball theatre troupe concentrating on the study of Foolish Humour have been chosen to be co-hosts of the New Fringe Factor (Do Fringe Shows have Talent?) TV Show that has been developed over the last seven years by Stephen Carew-Reid and the Late Thomas Graham Allwood with sponsorship from the INL News Group.

Joanne Tremarco and her partner Chris Murray hosted one of the many pilots of the New Fringe Factor (Do Fringe Shows have Talent?) TV Show filmed at the Scotsman Hotel on the 21st August, 2013 where Fringe Entertainers came along to watch classic moments filmed at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival and perform short performances and chat about their fringe show and their experiences at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

Woman in vagina outfit runs to rescue man in penis outfit

Woman in vagina outfit runs to rescue man in penis outfit

Performers cause offence dicking and fannying about on the streets of Glastonbury.

We spend a fair amount of time talking about penises and vaginas at Planet Ivy. The less liberally-minded, more mature amongst you might say too much. Whatever, dick-head. So when we saw this story in the Central Somerset Gazette about a man dressed as a penis getting mildly accosted by a passer-by, and a woman dressed as a vagina running to his aid, we felt finally, our time for news-reporting glory had come.

The incident occurred last Friday when actors from the Nomadic Academy of Fools – an odd-ball theatre troupe – were handing out flyers to promote two of their shows, ingeniously titled: Women Who Wank and The Penis Monologues. A member (yep) of the public was so offended by the sight of Chris Murray, dressed as a penis on Glastonbury High Street, that he yanked the head off the costume and threw it on the floor.

Witnessing her penis friend’s veritable circumcision, Joanne Tremarco – dressed quite equally disturbingly as a vagina – ran to his aid to try and tame the raging pedestrian. The police were called as the theatre group made their way back to their headquarters, and were told to avoid dressing like cocks in future. Their flyers were also confiscated, but you will be delighted to hear that Women Who Wank and The Penis Monologues went ahead as planned. I’m sure it was delightful.

Women Who Wank– Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2013

a USA Weekly News 100 Star Award Winner

“….. ‘Women Who Wank’ is not only entertaining but quite informative and reaches out into your inner soul….. one of the most unusual, provocative, outrageous … could say scandalous… but most of all one of the most professional and entertaining Fringe Shows we have seen for a long time at any fringe festival form around the world .. ‘Woman Who Wank’ … well earns its USA Weekly News 100 Star Award for being a fringe show which is way above the normal five-star standard….”..USAWeekly News.

Low Down

Part of the PBH Free Fringe, Women Who Wank happens in Cowgatehead, a hole in the wall that would be easy to miss, sandwiched between Underbelly and the Cowshed on Cowgate. It’s half ten at night, we’re tired, wired; some of us are a bit pissed. We’ve gathered in a small, boxy space that resembles nothing so much as a bomb shelter. There’s a pretty good crowd – evidently there are a lot of people interested in women who wank. Expectations are running high. One of the last people into the room is an extravagant, gaudy woman who talks with a posh slur as she swishes up and down the aisle, looking for a seat in the packed house, complaining about what she’s sure will be a shit show. She couldn’t be further from the truth.

What are our expectations for a show with such a provocative title? The population of Joanne’s audience is about two-thirds women, and the men are mostly here with dates. There are a few single men present. The atmosphere is sexually charged even before Joanne begins polarizing the room, calling us out, trying to uncover our secrets even as she hauls our curiosity up on stage for us to scrutinize. Bombs rain down on us from the show in the room above as we retreat into the wartime bunker where Joanne promises to shield us from harm. She is all over the place, mad-woman, character actress, saint of purity and prurient wanker, enticing us wickedly. Her improvisational skills are captivating as she traipses through her youth with us, uncovers moments of vulnerability and truth, and fences with a pair of particularly vociferous late-night hecklers with alternating severity and tenderness.

I won’t say too much about the content of this show because it’s my opinion that you should check it out and discover it for yourself – and, equally, as a totally improvised show, the content will be completely different on any given night. But after an hour that flew by, I’m tempted to go back and see what other secrets lurk within Joanne’s bunker. Reviewed by William Glenn 8th August 2013

Website : http://www.nomadicacademy.org

Foolish Who’s Who

WHAT IS FOOLING?

Fooling is a unique technique that introduces you to the architecture of your own personal inner stage, upon which you are able to perform on or in any space, and at any time, using just improvisation and your own imagination.

This work stretches past ego, allowing you to feel at ease in any situation and comfortable talking intimately with anyone in the audience, be them a beggar, king or queen. As a performer you slowly learn to play within this architecture, which Jonathan Kay calls “the Structure”. As you also learn about the atmosphere available in each part of the stage, you allow yourself to be influenced, and in doing so you as the performer surrenders to that experience to create whatever kind of ‘stage’ you are performing in, be it the street, in a church, theatre or in a living-room. The Structure is developed through the workshops. It is a way of moving through the stage area and meeting the unknown with a relaxed attitude.

Want to know more about the Fools of The Nomadic Academy?-

Joanne Tremarco paints bold images with oils and your imagination. She is a blundering psychic, a kamikaze perfectionist, a wild woman who is afraid of the dark, an unhealed healer, a lover of clean tea towels, a prolapsed catholic who dreams far too much whilst cycling her bike. She loves cleaning (but it takes too long), gardening and looking after other people’s children.

She loves performing without a parachute, making audiences laugh and cry.

You can see her in her one-woman show, Women Who Wank, at Festivals around the UK this year. To book ‘Women Who Wank’ contact here Aside from working with The Nomadic Academy for Fools, she also huffs and puffs her way through Physical Fest each year with her friends from Tmesis Theatre and she works from time to time for Friction Arts.

If Chris Murray were here, what would he do? How would Christopher Murray deal with this problem? Look! He left his shoes behind, lets walk a mile in them and see…just one of the many conversations I wish people would have after meeting me.

Jane Scott is 5’10″ tall, 36′,28′,36′ and likes animals and working for charity-

Danny Mullins is a musician who likes to fool around. He’s in his fifth year with the Academy for Fools. He’s currently enjoying teaching Edinburgh Fools Academy, hosting community sing song sessions and working with Edinburgh’s Beltaine Fire Society as a “red man”. Meaning everything that is RED! It’s tribal, it’s primal, passion, power, and Love. He’s working with the group to bring out their sensual and sexual energies by mixing in what he has learned from the “Awaken Love” Tantra group to develop the “Fool Around” workshops. Playful and also respectful, personal boundaries will be mindfully observed throughout: and stretched out gently. A touching and tickling performer, Danny also enjoys writing about himself from a detached “third person” perspective to make it sound as though he’s much more worldly-wise and well known than he actually is.

Katherine Smith performs foolish plays in foolish ways as the fool she says…

Who am I? A big O until we meet in the world of our imagination…

You want information? Well then, on a more practical level I’m a gardener, a recent Mumma, a wife, a performer, a piano player, a publisher and a writer.

With the Academy for Fools, I’m working on a play called the Living Museum of Marjorie – from which we’ll be performing characters and tantalising snippets during this festival for fools. …These Old Fools – they are sad and dusty old relics from bygone eras who can move into beauty full of wonder.

Bruce Knight is a performer and also looks after Spilsby Theatre in Lincolnshire. He worked for many years as a lighting technician.

He first began performing as an aerialist, on trapeze dressed as Elvis, when his circus hobby got out of hand! Since then he has played many characters on earth, directed community theatre projects and trained for several years with Jonathan Kay and also regularly performs as ‘Jim” with the Brighton based company Copperdollar.

Natalie Fee is a performer, poet and presenter, trained by Jonathan Kay in the art of the Fool. She performs regular improvised shows in theatres around Bristol, using music, humour and comedy to open up the challenges we face as individuals and as a global community.

Paul Scott is a ex-con, ex squaddie, 96.4% orangutan just like you, professional dog training instructor, painter, chainsaw carver, commentator and quite good with a needle and thread. Born as a wooly-back and lifelong holy devotee to Liverpool FC. He likes photography, travelling, rainforests, sarcasm, sports cars, Doctor Who, 5 Rhythms Ecstatic Dance, music festivals, Scuba diving, power tools, medical marijuana, animals, Pink Floyd, potatoes, tantric sex, Sumatra and builders tea. He is inspired by Kenny Dalglish, Osho, David Attenborough, Maharaji , Obi-wan- kenobi , Salvador Dali, Hanuman and Bill Hicks. Some things he would like to see blown to thousands of pieces are Old Trafford, Crufts, Schools, Scotland yard, Animal hunters, Inland Revenue, DVLA, Ascot and festival security guards.

Is It Normal to Masturbate When You’re Married?http://psychcentral.com/lib/is-it-normal-to-masturbate-when-youre-married/000103

By Michael Ashworth, Ph.D.

There is absolutely no reason to feel guilty for masturbating even though you are married. Most men and women do indeed continue to masturbate when they are in a relationship, and it does not mean that there is anything wrong. In fact, research shows that those people who masturbate more also have more (and more satisfying) sex. People have sex, as well as masturbate, for all sorts of reasons. Often men and women feel like having an orgasm or pleasuring themselves as a quick stress reliever, as a “pick-me-up”, or just because they are very aroused but don’t want to go through the whole process of sex. Masturbating is also a great way to learn about your own body, which invariably makes for better sex with a partner. Men can use masturbation as a way to learn how to control their orgasms, while women can learn how to have orgasms more easily.

Sometimes people feel that if everything was perfect in a sexual relationship, then neither partner would “need” to masturbate. Nothing could be further from the truth. Simply put, good sex begets more good sex — in all its forms. In fact, many couples masturbate together and find it a very enjoyable part of their relationship. Honestly, there is no need to feel guilty. Listen to the good doctor: Masturbation is good for you!

http://ehealthforum.com/health/are-there-other-women-who-do-not-masturbate-t292785-a1.html

Re: how often do women masturbate? and do all women do it?

http://www.thestudentroom.co.uk/showthread.php?t=1298309

Answers:

1. Well I have sex with my bf everyday, sometimes twice a day when I’m with him (I like to wake him up with head and give him a proper start to the day) and we’re in a LDR at the moment so prob about twice a week when the waiting gets too much and I’m too horny to wait anymore,

2. Every day (I love how female masturbation is still a mystery).

3. I swear there is a thread on this every single day. Yes, majority do it, and how often depends on the person, same as men./thread

4. Once every 4 days…

5. never. and im not even joking.

6. Have you climaxed yet OP?

7. the majority do, and many of those who say they don’t lie!! frequency is different for each woman but at the moment it’s been 3 weeks since i has sex with my bf so at least every other day if not everyday!! when the sex is there once a week if at all. i also **** a lot when i’m stressed so exams add to my horniness.

8. Almost never. Haven’t really got the hang of it.

9. Lots of people do, surely this has all been said a million times before?

10. Lots of people do, surely this has all been said a million times before.

11. Everyday tbh … is that bad for you?

12. Something I never thought I’d hear from anyone.

13. last time I check, 65% were doing it.

14. once a day. sometimes twice if I have a day off. Orgasm-wise it is the best, no man can ever get anywhere near unfortunately (even though it can be great with a partner, I never reach the same level).I cannot believe there are women that never do it!

15. Couple of times a week when I’m at home (with my boyfriend), almost every day when we’re apart. Not all women do it, but if they don’t I assume that’s because they haven’t figured out how to get off yet, it can take a while.

TART, London-based San Franciscan, David Mills, is a spiky recent import from the cabaret circuit, delivering his caustically sarcastic stand-up from a bar stool.

By JAY RICHARDSON – Friday, 24th August 2012- TART, London-based San Franciscan, David Mills, is a spiky recent import from the cabaret circuit, delivering his caustically sarcastic stand-up from a bar stool. –David Mills is Smart Casual -With his sharp, refined appearance, smooth, honeyed tones and rampant bitchiness he’s a strange mix of the measured and the transgressive. The package is charismatic and authoritative, sidestepping the paucity of some of his material. There’s little to recommend his withering demand for “fat bitch” Stephen Fry to simply “f*** off”, save for the refreshing frisson of its unorthodoxy, to which he adds a further, unlikely slur against the national treasure. Attitude alone often carries him through. Celebrities are a favourite target, comparisons between them typically insulting both parties. Minority groups take a few slaps too, occasionally with wit and daring, elsewhere simply for the sake of it.

He does have some good jokes, on the most unlikely aspect of the Thor movie, superheroes clearly a preoccupation as he aligns certain fashion designers with villains from the Marvel comics universe. There’s a compelling thread in which he asks why the gay rights movement should settle for equality rather than celebrate difference but it’s underdeveloped. A flawed but still promising debut.

A review has been made by the USA Weekly News on the performance by Eilin O’Dea of James Joyce’s Ulysses Molly Bloom’s soliloquy at the end of the James Joyce’s Ulysses’. This is recognised as one of the most famous female narratives in modern literature, which was performed by Eilin O’Dea and directed by Liam Carney at the Teachers Club 36 Parnell Square West Dublin 1, from the 25th September – 6th October, 2008.

This famous narrative which has been used as the basis of songs, re-appeared in movies, quoted in other literary works and in terms of its effect on Irish culture is one of the most difficult narratives for an actor to perform. Eilin Odea performs Molly Bloom’s otherwise silent voice to bear her soul on life, love, sex and loneliness. This has been done with absolute artistic genius by Eilen Odea in a genuine authentic way. Having heard Eilin Odea as Molly Bloom, it is hard to imagine any other actor performing this difficult narrative in anyway near the standard set by Eilin Odea. In effect Eilin Odea has become the real Molly Bloom is this absolute stunning academy award style performance which will no doubt receive a standing ovation from audiences all around the world.

The USA Weekly News is compelled to give Eilin’s performance of Molly Bloom the hightest industry award that is on offer. There is absolutely no doubt of her receiving the normal top five star industry award. However, the USA WEEKLY NEWS has a special 100 star award for performances that are in a class of their own.

Eilin’s performance of Molly Bloom is one of these performances.

The USA WEEKLY NEWS is confident that when Eilin Odea takes her performance of Molly Bloom to London, New York, Australia and the rest of the world, the play will have a very long and successful season.

Awards from the USA WEEKLY NEWS to Eilin Odea as Molly Bloom directed by Liam Carney : The normal Industry 5 star award plus the USA WEEKLY NEWS special 100 star award for being is class far above the standard to the normal five star ward performance.

Sincere congradulations from the USA WEEKLY NEWS…..

A performance not to be missed….

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (1882-1941)

Irish novelist, noted for his experimental use of language in such works as ULYSSES (1922) and FINNEGANS WAKE (1939). During his career Joyce suffered from rejections from publishers, suppression by censors, attacks by critics, and misunderstanding by readers. From 1902 Joyce led a nomadic life, which perhaps reflected in his interest in the character of Odysseus. Although he spent long times in Paris, Trieste, Rome, and Zürich, with only occasional brief visit to Ireland, his native country remained basic to all his writings.

“But when the restraining influence of the school was at a distance I began to hunger again for wild sensations, for the escape which those chronicles of disorder alone seemed to offer me. The mimic warfare of the evening became at last as wearisome to me as the routine of school in the morning because I wanted real adventures to happen to myself. But real adventures, I reflected, do not happen to people who remain at home: they must be sought abroad.” (from Dubliners)

James Joyce was born in Dublin as the son of John Stanislaus Joyce, impoverished gentleman, who had failed in a distillery business and tried all kinds of professions, including politics and tax collecting. Joyce’s mother, Mary Jane Murray, was ten years younger than her husband. She was an accomplished pianist, whose life was dominated by the Roman Catholic Church and her husband. In spite of the poverty, the family struggled to maintain solid middle-class facade.

From the age of six Joyce, was educated by Jesuits at Clongowes Wood College, at Clane, and then at Belvedere College in Dublin (1893-97). Later the author thanked Jesuits for teaching him to think straight, although he rejected their religious instructions. At school he once broke his glasses and was unable to do his lessons. This episode was recounted in A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN (1916). In 1898 he entered the University College, Dublin, where he found his early inspirations from the works of Henrik Ibsen, St.Thomas Aquinas and W.B. Yeats. Joyce’s first publication was an essay on Ibsen’s play When We Dead Awaken. It appeared in Fortnightly Review in 1900. At this time he began writing lyric poems.

After graduation in 1902 the twenty-year-old Joyce went to Paris, where he worked as a journalist, teacher and in other occupations in difficult financial conditions. He spent in France a year, returning when a telegram arrived saying his mother was dying. Not long after her death, Joyce was traveling again. He left Dublin in 1904 with Nora Barnacle, a chambermaid (they married in 1931), staying in Pola, Austria-Hungary, and in Trieste, which was the world’s seventh busiest port. Joyce gave English lessons and talked about setting up an agency to sell Irish tweed. Refused a post teaching Italian literature in Dublin, he continued to live abroad.

The Trieste years were nomadic, poverty-stricken, and productive. Joyce and Nora loved this cosmopolitan port city at the head of the Adriatic Sea, where they lived in a number of different addresses. During this period Joyce wrote most of DUBLINERS (1914), all of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the play, EXILES (1918), and large sections of Ulysses. Several of Joyce’s siblings joined them, and two children, Giorgio and Lucia, were born. The children grew up speakin the Trieste dialect of Italian. Joyce and Nora stayed together althoug Joyce fell in love with Anny Schleimer, the daughter of an Austrian banker, and Roberto Prezioso, the editor of the newspaper Il Piccolo della Sera, tried to seduce Nora. After a short stint in Rome in 1906-07 as a bank clerk ended in illness, Joyce returned to Trieste.

In 1907 Joyce published a collection of poems, CHAMBER MUSIC. The title was suggested, as the author later stated, by the sound of urine tinkling into a prostitute’s chamber pot. The poems have with their open vowels and repetitions such musical quality that many of them have been made into songs. “I have left my book, / I have left my room, / For I heard you singing / Through the gloom.” Joyce himself had a fine tenor voice; he liked opera and bel canto.

In 1909 Joyce opened a cinema in Dublin, but this affair failed and he was soon back in Trieste, still broke and working as a teacher, tweed salesman, journalist and lecturer. In 1912 he was in Ireland, trying to persuade Maunsel & Co to fulfill their contract to publish Dubliners. The work contained a series of short stories, dealing with the lives of ordinary people, youth, adolescence, young adulthood, and maturity. The last story, ‘The Dead’, was adapted into screen by John Huston in 1987.

It was Joyce’s last journey to his home country. However, he had became friends with Ezra Pound, who began to market his works. In 1916 appeared Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, an autobiographical novel. It apparently began as a quasi-biographical memoir entitled Stephen Hero between 1904 and 1906. Only a fragment of the original manuscript has survived. The book follows the life of the protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, from childhood towards maturity, his education at University College, Dublin, and rebellion to free himself from the claims of family and Irish nationalism. Stephen takes religion seriously, and considers entering a seminary, but then also rejects Roman Catholicism. “-Look here, Cranly, he said. You have asked me what I would do and what I would not do. I will tell you what I will do and what I will not do. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it call itself my home, my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using my defence the only arms I allow myself to use – silence, exile, and cunning.”At the end Stephen resolves to leave Ireland for Paris to encounter “the reality of experience”. He wants to establish himself as a writer.

There once was a lounger named Stephen

Whose youth was most odd and uneven

—He throve on the smell

—Of a horrible hell

That a Hottentot wouldn’t believe in.

(Joyce’s limerick on the book’s protagonist)

At the outset of the First World War, Joyce moved with his family to Zürich, where Lenin and the poet essayist Tristan Tzara had found their refuge. Joyce’s WW I years with the legendary Russian revolutionary and Tzara, who founded the dadaist movement at the Cabaret Voltaire, provide the basis for Tom Stoppard’s play Travesties (1974).

In Zürich Joyce started to develop the early chapters of Ulysses, which was first published in France, because of censorship troubles in the Great Britain and the United States, where the book became legally available 1933. The theme of jealousy was based partly on a story a former friend of Joyce told: he claimed that he had been sexually intimate with the author’s wife, Nora, even while Joyce was courting her. Ulysses takes place on one day in Dublin (June 16, 1904) and reflected the classic work of Homer (fl. 9th or 8th century BC?).

The main characters are Leopold Bloom, a Jewish advertising canvasser, his wife Molly, and Stephen Dedalus, the hero from Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. They are intended to be modern counterparts of Telemachus, Ulysses, and Penelope. Barmaids are the famous Sirens. One of the models for Bloom was Ettore Schmitz (Italo Svevo), a novelist and businessman who was Joyce’s student at the Berlitz school in Trieste. The story, using stream-of-consciousness technique, parallel the major events in Odysseus’ journey home. However, Bloom’s adventures are less heroic and his homecoming is less violent. Bloom makes his trip to the underworld by attending a funeral at Glasnevin Cemetary. “We are praying now for the repose of his soul. Hoping you’re well and not in hell. Nice change of air. Out of the fryingpan of life into the fire of purgatory.”The paths of Stephen and Bloom cross and recross through the day.Joyce’s technical innovations in the art of the novel include an extensive use of interior monologue; he used a complex network of symbolic parallels drawn from the mythology, history, and literature.

From 1917 to 1930 Joyce endured several eye operations, being totally blind for short intervals. (According to tradition, Homer was also blind.) In March 1923 Joyce started in Paris his second major work, Finnegans Wake, suffering at the same time chronic eye troubles caused by glaucoma. The first segment of the novel appeared in Ford Madox Ford‘s transatlantic review in April 1924, as part of what Joyce called Work in Progress. Wake occupied Joyce’s time for the next sixteen years – its final version was completed late in 1938. A copy of the novel was present at Joyce’s birthday celebration on February 1939.

Joyce’s daughter Lucia, born in Trieste in 1907, became Carl Jung‘s patient in 1934. In her teens, she studied dance, and later The Paris Times praised her skills as choreocrapher, linguist, and performer. With her father she collaborated in POMES PENYEACH (1927), for which she did some illustrations. Lucia’s great love was Samuel Beckett, who was not interested in her. In the 1930s, she started to behave erratically. At the Burghölz psychiatric clinic in Zurich, where Jung worked, she was diagnosed schizophrenic. Joyce was left bitter at Jung’s analysis of his daughter – Jung thought she was too close with her father’s psychic system. In revenge, Joyce played in Finnegans Wake with Jung’s concepts of Animus and Anima. Lucia died in a mental hospital in Northampton, England, in 1982.

After the fall of France in WWII, Joyce returned to Zürich, where he died on January 13, 1941, still disappointed with the reception of Finnegans Wake. The book was partly based on Freud’s dream psychology, Bruno’s theory of the complementary but conflicting nature of opposites, and the cyclic theory of history of Giambattista Vico (1668-1744).

Finnegans Wake was the last and most revolutionary work of the author. There is not much plot or characters to speak of – the life of all human experience is viewed as fragmentary. Some critics considered the work masterpiece, though many readers found it incomprehensible. “The only demand I make of my reader,” Joyce once told an interviewer, “is that he should devote his whole life to reading my works.” When the American writer Max Eastman asked Joyce why the book was written in a very difficult style, Joyce replied: “To keep the critics busy for three hundred years.” The novel presents the dreams and nightmares of H.C.Earwicker (Here Comes Everywhere) and his family, the wife and mother Anna Livia Plurabelle, the twins Shem/Jerry and Shaun/Kevin, and the daughter Issy, as they lie asleep throughout the night. In the frame of the minimal central story Joyce experiments with language, combines puns and foreign words with allusions to historical, psychological and religious cosmology. The characters turn up in hundreds of different forms – animal, vegetable and mineral. Transformations are as flexible as in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The last word in the book is ‘the’, which leads, by Joyce’s ever recurrent cycles, to the opening word in the book, the eternal ‘riverrun.’

Although the events are set in the Dublin suburb of Chapelizod, the place is an analogy for everywhere else. Wake’s structure follows the three stages of history as laid out by Vico: the Divine, the Heroic, and Human, followed period of flux, after which the cycle begins all over again: the last sentence in the work runs into the first. The title of the book is a compound of Finn MaCool, the Irish folk-hero who is supposed to return to life at some future date to become the savior of Ireland, and Tim Finnegan, the hero of music-hall ballad, who sprang to life in the middle of his own wake.

For further reading: James Joyce by Herbert Gorman (1939); Introducing James Joyce, ed. by T.S. Eliot (1942); Stephen Hero, ed. by Theodore Spencer (1944); James Joyce by W.Y. Tindall (1950); Joyce: The Man, the Reputation, the Work by M. Maglaner and R.M. Kain (1956); Dublin’s Joyce by Hugh Kenner (1956); My Brtother’s Keeper by S. Joyce (1958); James Joyce by Richard Ellmann (1959); A Readers’ Guide to Joyce (1959); The Art of James Joyce by A.W. Litz (1961); Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses by R.M. Adams (1962); J. Joyce-again’s Finnegans Wake by B. Benstock (1965); James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’: Critical Essays, ed. by Clive Hart and David Hayman (1974); A Conceptual Guide to ‘Finnegans Wake‘ by Michael H. Begnal and Fritz Senn (1974); James Joyce: the Citizen and the Artist by C. Peake (1977); James Joyce by Patrick Parrinder (1984); Joyce’s Anatomy of Culture by Cheryl Herr (1986); Joyce’s Book of the Dark: ‘Finnegans Wake by John Bishop (1986); Reauthorizing Joyce by Vicki Mahaffey (1988); ‘Ulysses’ Annotated by Don Gifford (1988); An Annotated Critical Bibliography of James Joyce, ed. by Thomas F. Staley (1989); The Cambridge Companion to James Joyce, ed by Derek Attridge (1990); Joyce’s Web by Margot Norris (1992); James Joyce’s ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’ by David Seed (1992); Critical Essays on James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake ed. by Patrick A. McCarthy (1992); James Joyce and the Language of History: Dedalus’s Nightmare by Robert E. Spoo (1994), Gender in Joyce, ed. by Jolanta W. Wawrzycka (1997) ; A Companion to James Joyce’s Ulysses, ed. by Margot Norris (1999); Toiseen maailmaan. James Joycen novelli “Kuolleet” kirjallisuustieteen kohteena by Pekka Vartiainen (1999); The Years of Bloom: James Joyce in Trieste, 1904-1920 by John McCourt (2000) – See also: Little Blue Light, Samuel Beckett,William Butler Yeats, Marcel Proust

Selected works:

- CHAMBER MUSIC, 1907

- DUBLINERS, 1914 – Dublinilaisia – film Dead (1987), based on the last story in the collection, dir. by John Huston, starring Anjelica Huston

- A PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN, 1916 – Taiteilijan omakuva nuoruuden vuosilta (trans. into Finnish by Alex Matson) – film 1979, dir. by Joseph Strick, starring Bosco Hogan, T.P. McKenna, John Gielgud

- EXILES, 1918

- ULYSSES, 1922 – Odysseus (trans. into Finnish by Pentti Saarikoski) – film 1967, dir. by Joseph Strick, starring Barbara Jefford, Molo O’Shea, Maurive Roeves, T.P. McKenna

- POMES PENYEACH, 1927

- COLLECTED POEMS, 1936

- FINNEGANS WAKE, 1939 – film 1965, dir. by Mary Ellen Bute

- STEPHEN HERO, 1944

- THE PORTABLE JAMES JOYCE, 1947

- THE ESSENTIAL JAMES JOYCE, 1948

- THE LETTERS OF JAMES JOYCE, 3 vols., 1957-66

- THE CRITICAL WRITINGS, 1959

- ‘LIVIA PRULABELLA’ – THE MAKING OF A CHAPTER, 1960

- A FIRST DRAFT VERSION OF ‘FINNEGANS WAKE’, 1963

- THE LETETRS OF JAMES JOYCE, 3 vols., 1957-66

- GIACOMO JOYCE, 1968

- SELECTED LETTERS OF JAMES JOYCE, 1975

- THE JAMES JOYCE ARCHIVES, 63 vols., 1977-80

- ULYSSES: A READER’S EDITION, 1997 (ed. by Danis Rose

I want to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book,” James Joyce told his friend the artist Frank Budgen as he was laboring on his epic novel Ulysses in Zurich.

In voluntary exile from his native Ireland, Joyce wrote with Thom’s Directory, a Dublin city reference book at his elbow and often sought in letters to relatives and friends precise details of various locations. Dublin also provided the backbone for Joyce’s other major works: Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Finnegans Wake. “…the personality of the city is present in an almost human way,” notes the Trinity College scholar David Norris, “lightly buried under the texture of the prose.”

In recent years I have discovered Dublin by literally walking in the steps of James Joyce and his characters and in so doing have enjoyed a dual love affair. I always carry a copy of Ulysses and one of the literary maps or guides available at Dublin’s proliferating shrines to the writer whose books were proscribed during his lifetime.

Ulysses takes place on the single day and evening of June 16, 1904 which commemorates the author’s first walk about town with Nora Barnacle who would become his life companion. Over the last 20 years the date has been celebrated as Bloomsday in honor of Leopold Bloom, the hero of the novel. Bloom, a Jewish advertising salesman, wanders about the city, sometimes crossing paths with Stephen Dedalus, a young writer who is Joyce’s alter ego.

The Dublin inhabited by Joyce and his Everyman was an Edwardian backwater of the British Empire, a city of gaslight, horsedrawn carriages, outdoor plumbing and many unpaved streets. The magnificent Georgian houses and squares built in the 18th century, Dublin’s golden age, for the Anglo-Irish landowners attending the short-lived Irish Parliament had been lapsing into slums. Grinding poverty confronted faded elegance. Revolution was more than a decade in the future. The Irish Literary Revival led by William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory was unfolding in theaters and meeting rooms but the prickly 22-year-old Joyce did not participate in the movement.

This Dublin, recalls the actress Fionnula Flanagan, was “frozen in amber like a fly until World War II.” Then real estate developers, unrestrained by civic pride or preservation instincts, demolished many of the architectural gems. About 20 years ago, dedicated urbanists like David Norris, professor of English studies at Trinity College Dublin and a member of the Irish Senate, began to reverse the destructive tide. The centenary of Joyce’s birth in 1982 further stimulated efforts at recognizing the writer’s work and preserving his environment.

As a result Dublin today is a rewarding destination for Joycean pilgrims whether scholars or novitiates. Despite the lacunae caused by those earlier wrecking balls Joyce’s Hibernian Metropolis survives in the midst of a vibrant Irish capital he would scarcely recognize. Ireland in the 1990’s has become one of the most flourishing economies in Europe. With political and cultural straitjackets removed, Dublin is the magnet for young writers, film makers, artists and even food connoisseurs.

The very best time to explore Dublin through James Joyce’s life and fiction is on a Bloomsday or the week leading up to it, an enlarged celebration called Bloomstime. The capricious Irish weather is inclined to present a sunny face in late spring and apart from scheduled literary events, the streets are filled with actors and mimes giving impromptu performances.

Still, any season is conducive to discovering James Joyce on his own turf. Just remember to take an umbrella and puddleproof footwear.

Dublin is a pedestrian’s city, welcoming to the inquisitive saunterer. Haste has not yet seeped into the Irish consciousness nor have Dubliners speeded up to the pace of New York or London. Robert Nicholson, curator of the James Joyce Museum, reckons that Leopold Bloom covered 18 miles of city streets in as many hours, about half on foot, the rest by tram and horse-drawn carriage.

Bloom did not follow a straight course in his meanderings. Moreover, Nicholson reminds us, the third major character, Molly Bloom, spends practically the entire time in her bed. I am therefore proposing a series of walks, loosely but not exclusively based on chapters in Ulysses. There are references to Joyce’s Dubliners and Portrait as well because numerous characters appear in more than one book and their hapless lives are played out in the heart of Dublin and some of its outlying districts.

These excursions are by no means comprehensive and their design is idiosyncratic since it is based on my own literary infatuations. Not everyone will want to see the back wall of the building in which Nora Barnacle worked as a chambermaid or choose to eschew a search for Nighttown and Bella Cohen’s vanished brothel.

In the course of a day, the literary tourist like the fictional folk in Joyce’s other books will repeatedly encounter the River Liffey. His “dear dirty Dublin” is one of those cities whose aspect is determined by a river–and a dear dirty river it is, too. The Liffey rises in the Wicklow mountains to the south, descends to bisect the city and them empties into the Irish Sea. Joyce made the Liffey a character in Finnegans Wake, his last and most challenging novel. Anna Livia Plurabelle, the matriarchal figure of the Wake, is at times transposed into the Liffey. (Livia is the Latin name for Liffey.)

O

tell me all about

Anna Livia! I want to hear all

about Anna Livia. Tell me all. Tell me now. You’ll die

when you hear. [FW 196.1]

Sources are identified as follows: Dubliners (D), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (PA), Ulysses (U), Finnegans Wake (FW).

EXCURSION 1:

Telemachus, Nestor, Nausicaa, Lotuseaters

Logic would seem to dictate the center of the city for an initial excursion devoted to an urban author. I propose instead an early morning trip to suburban Sandycove and the James Joyce Museum located in the Martello Tower, the setting for the opening chapter of Ulysses.

At the Westland Row station for DART, Dublin’s above-ground train system, head in the southerly direction of Bray for a 20-minute ride to Sandycove. Leaving the station take the nearest side street and proceed toward the water (“the snot-green sea” of Dublin Bay.) Turn right and walk along the coast road toward the round gray fortification. The Martello Tower was built in 1804 by the British as a safeguard against a feared Napoleonic invasion that never materialized.

In the summer of 1904, Oliver St. John Gogarty, a young medical student and poet rented the tower which had just been demilitarized by the British army and invited James Joyce to stay there with him. During the brief visit the friendship ruptured. Joyce repaid Gogarty by casting him as the insensitive character of Buck Mulligan in Ulysses.

The entrance to the James Joyce Museum is tucked behind a white-walled residence of stark modern design by Michael Scott, a noted Dublin architect. The ground floor of the museum is given to a bookstore, a gift shop and exhibits of memorabilia. All are worth scrutiny but best climb straight to the roof of the tower where on a Bloomsday Joyceans will be perched on the parapets reading aloud.

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him on the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned:

-Introibo ad altare Dei.

Halted, he peered down the dark winding stairs and called out coarsely:

–Come up, Kinch! Come up, you fearful jesuit!

After walking around the parapet and gazing out to sea in recollection of Stephen Dedalus, climb down the spiral staircase to the Round Room, the principal living area and the setting for the breakfast scene. A ceramic black panther stands guard in front of the hearth, a reminder of the nightmare suffered by the English guest Haines (and his original Samuel Chenevix Trench) which prompted the gun blasts that provoked Stephen (and James Joyce) into leaving the tower.

Now we can peruse the exhibits on the first floor. They range from a pandybat such as the one administered to Stephen at Clongowes Wood College in the first chapter of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man to numerous manuscripts, photographs and letters exchanged between James and Nora Joyce and their friends. An essential purchase in the bookstore is Robert Nicholson’s The Ulysses Guide: Tours Through Joyce’s Dublin.

Leaving the Tower and bearing left, repeat after Buck Mulligan the ballad of joking jesus. This should take us to the Forty-Foot perched at the edge of the cliff. Now as in Joyce’s time hardy members of the Sandycove Bathers Association plunge into the scrotumtightening sea [U4/78] in weather foul or fair. On Bloomsday, in the interest of fidelity to the text, Joyceans follow Buck Mulligan and take the leap in the buff.

In the novel Stephen parts company with Mulligan and Haines and proceeds to his teaching job at a school in Dalkey, a distance of about one mile. Nicholson conjectures that he walked along Sandycove Avenue East to Breffni Road and its continuation on Ulverton Road to the village of Dalkey, celebrated in the works of several Irish writers, in particular the playwright Hugh Leonard.

At the corner of Dalkey Avenue and Old Quarry is “Summerfield”, an estate once occupied by the Clifton School. There Joyce instructed the sons of wealthy Protestant families for a brief period in 1904 and used its obnoxious headmaster as a model for Mr. Deasy.

–Ireland, they say, has the honour of being the only country which never persecuted the jews…do you know why? [Mr. Deasy asked Stephen]

–Because she never let them in, Mr. Deasy said solemnly.

A coughball of laughter leaped from his throat dragging after it a rattling chain of phlegm. [U30/437]

Walk along Dalkey Avenue, turning left into Cunningham Road until the Dalkey Railway Station. Take the train in the northbound direction City-Howth until the Landsdowne Road station. In June 1904 Joyce was living in a rented room at 60 Shelbourne Road.

Turn right from the station and proceed via Newbridge Avenue toward the Sandymount Strand beach. In Chapter 13 Nausicaa Leopold Bloom observed Gerty MacDowell at twilight seated on the rocks. En route, we will pass the Church of St. Mary Star of the Sea. Its Benediction service furnishes the background parody for Bloom’s and Gerty’s silent flirtation.

Then they sang the second verse of the Tantum Ergo and Canon O’Hanlon got up again and censed the Blessed Sacrament and knelt down and he told Father Conroy that one of the candles was going to set fire to the flowers and Father Conroy got up and settled it all right and she could see the gentleman winding his watch and listening to the works and she swung her leg more in and out. [U296/552]

As the priest restores the Blessed Sacrament to the tabernacle and the choir sings “Laudate Dominum omnes gentes” fireworks from a bazaar nearby illuminate the sky behind the church causing Gerty to reveal her underwear and Bloom to satisfy his passion.

And then a rocket sprang and bang shot blind blank and O! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures and it gushed out of it a stream of rain gold hair threads and they shed and ah! they were all greeny dew stars falling with golden, O so lovely, O, soft, sweet, soft! [U300/736]

Earlier in the day Stephen Dedalus had walked by the very same spot meditating (Chapter 3 Proteus) and back on Newbridge Avenue Leopold Bloom had joined the mourners bound for Paddy Dignam’s funeral (Chapter 6 Hades.)

I suggest we return to the train station and then to the center of the city. Get off at the Westland Row station where we started. At the foot of Westland Row, Sweny’s the chemist at 1 Lincoln Place still dispenses the fragrant lemon soap Bloom bought for Molly in the Lotuseaters episode.

Mr. Bloom raised a cake to his nostrils. Sweet lemony wax. –I’ll take this one, he said. That makes three and a penny. [U69/512]

Lemon soap is the Joycean’s emblematic souvenir. Expect to pay an Irish pound or more.

EXCURSION 2:

Calypso, Penelope, Ithaca, Wandering Rocks

Let us go straightaway to the James Joyce Centre at 35 North Great George’s Street to pick up literature and guidance, particularly the map So this is Dyoublong?/ The City of Dublin in the Writings of James Joyce. The Centre is the hub of Bloomsday events and of other literary activities the year round. Ken Monaghan, son of Joyce’s sister May, discourses with brutal frankness on the family’s tragic history and leads a tour of the neighborhood.

The rose-brown brick mansion with its door colored in robin’s egg blue stands in the middle of a block of Georgian houses developed in the late 1700’s for Protestant landowners when they came to town to attend the Irish Parliament. In 1800 the Act of Union legislated in Westminster abolished that body; the aristocrats gave up their urban residences and during the 19th century the elegant quarters began to decay.

In its time many notables lived in the houses along the street. The plaque at Number 38 announces that Sir John Pentland Mahaffy, provost of Trinity College and tutor of Oscar Wilde, was one such resident. Mahaffy disapproved of Joyce, a student at University College, the Catholic institution on St. Stephen’s Green and cited him as proof that “it was a mistake to establish a separate university for the aborigenes of this island__for the corner-boys who spit in the Liffey.”

Twenty years ago, David Norris bought a house across the street and was instrumental in efforts to retrieve the block. Norris found a link to Ulysses that led to the founding of the Centre, thereby saving Number 35 from demolition. In 1904, one Dennis MaGinnis had operated a dancing school on the ground floor under the Italianized name of Professor Denis J. Maginni. Joyce turned him into one of the transient characters in his novel.

Framing the entrance to the tearoom at the back of the Centre is the door of 7 Eccles Street, holiest of Ulysses icons. Joyce gave this nearby address of his loyal friend John Francis Byrne to the Blooms in the novel. There the reader first meets Leopold in Chapter 4 Calypso when he prepares the “mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine.” [U 45/1]

Upstairs in her bedroom Molly Bloom has her adulterous interlude with Blazes Boylan and in a 30-page reverie concludes the book with an affirming “..and yes I said yes I will Yes.” [U643/1608]

At the head of North Great George’s Street is Belvedere College on Great Denmark Street. Joyce attended the Jesuit school from the ages of 11 to 16 after his father wheedled a scholarship for him from Father John Conmee, the headmaster. The priest was rewarded with roles in Portrait and Ulysses. Chapters 2 to 4 of Portrait take place at this 1786 Adam-style building which, like the Joyce Centre, boasts interior plasterwork by the noted stuccadore Michael Stapleton. From the street one can glimpse the chapel in which Stephen Dedalus listens to a terrifying sermon on hell. Until 1960 students at Belvedere were discouraged from reading the work of its most famous alumnus.

The Wandering Rocks episode of Ulysses begins here.

The superior, the very reverend John Conmee S.J. reset his smooth watch in his interior pocket as he came down the presbytery steps. Five to three.

Rather than follow his journey through Dublin I prefer to linger in this neighborhood which has a wealth of identification with Joyce’s writing.

Proceed right on Great Denmark Street for one block and turn left into Upper Gardiner Street to St.Francis Xavier Church. The real-life Father Conmee served as its superior. In Portrait, Stephen struggles to decide whether he has a vocation.

He was passing at that moment before the Jesuit house in Gardiner Street and wondered vaguely which window would be his if he ever joined the order. [PA Chapter 4]

In the Dubliners story Grace, the businessmen’s retreat__ “washing the pot” on a Thursday evening– is held in this church.

Take the first left into Dorset Street. Eccles Street is the second street at the right. The Mater Private Hospital occupies the site of Number 7. On the left side of Dorset is Hardwicke Place and St. George’s Church. This Protestant house of worship serves as a marker in several chapters of Ulysses __as Bloom sets out for the butcher, visits Bella Cohen’s brothel in Tyrone Street and, in the penultimate chapter, when he and Stephen part after midnight at the house in Eccles Street.

“The belfry of St. George’s Church sent out constant peals” on a summer Sunday morning in the Dubliners story The Boarding House (at 29 Hardwicke Street,) stiffening Mrs. Mooney’s resolve to shame Mr. Doran into marrying her daughter.

Hardwicke Street dead ends at Frederick Street. Turn left one block until Parnell Square (Rutland Square in Ulysses time as Paddy Dignam’s funeral procession wends its way to Glasnevin Cemetery.) The Writers Museum at the north end of the square merits a serious visit. A center of the Irish literary tradition, it includes a bookshop, an antiquarian book search service and a pleasant cafeteria.

Oliver St. John Gogarty’s home is at Number 5 Parnell Square across the street from the Rotunda Hospital, a respected medical facility since 1745 but more noteworthy in Joyce’s writing for its concert hall. The Gate Theatre on Cavendish Row, also part of the Rotunda complex, maintains its legendary reputation for classical and avant-garde productions.

At the base of the square the Augustus Saint-Gaudens statue of Charles Stewart Parnell, heralds the start of O’Connell Street, the great wide boulevard of Dublin’s north side. In Joyce’s time it was Sackville Street. Parnell, the patriot who led the Home Rule Movement in the 1880’s and was toppled by a love affair, is a defining figure in Joyce’s political consciousness. He reappears constantly in Joyce’s writing, most pointedly in the Christmas dinner scene in the first chapter of Portrait and in the Dubliners story Ivy Day in the Committee Room.

At the Gresham Hotel at the top of O’Connell Street Joyce set the epiphanic scene in the Dubliners story The Dead. Gabriel and Gretta Conroy spend the night at the Gresham after his aunts’ party. In their room the young husband learns of his wife’s earlier love. Gabriel stands at the window as the story concludes.

His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

Turning from the sublime to the tacky, Joyce would surely have been appalled by the statue purporting to represent his heroine Anna Livia in a pool of water in the middle of O’Connell Street. Dubliners who are much given to nicknaming their properties refer to the monument as “the floozy in the Jacuzzi.”

EXCURSION 3:

Aeolus, Lestrygonians, Scylla and Charybdis,

Wandering Rocks, Oxen of the Sun.

Let us catch up with Leopold Bloom at noon IN THE HEART OF THE HIBERNIAN METROPOLIS in front of the General Post Office on O’Connell (Sackville) Street. He is returning from Paddy Dignam’s funeral, an excursion we will take later on. In Bloom’s time, a column in the middle of the street commemorated the British victory at Trafalgar in 1805 and served as one of the city’s important transportation hubs.

*Before Nelson’s Pillar trams slowed, shunted, changed trolley, started for Blackrock, Kingstown and Dalkey…begins the Aeolus chapter. Right and left parallel clanging ringing a doubledecker and a singledeck moved from their railheads, swerved to the down line, glided parallel.[U 96/1]

(Later in the chapter, under the heading DEAR DIRTY DUBLIN Stephen Dedalus will recount “The Parable of the Plums” about two elderly women climbing the pillar’s spiral staircase to get the best views of Dublin.)

Admiral Lord Nelson, “the onehandled adulterer” and his base were destroyed in a mysterious act of sabotage in 1966, and the trams have long since been replaced by buses. But the General Post Office, functioning with notable efficiency, remains a sacred landmark in Irish history. On Easter Monday in 1916 when Joyce was living in Zurich working on Ulysses, nationalist insurgents occupied the building for a bloody week of rebellion. Lines from the Proclamation of Independence read by the poet Patrick Pearse are posted near the main door. As a college student Joyce had briefly studied the Irish language with Pearse whom the British would execute for his part in the Rising.

Bloom heads for Prince’s Street on the south side of the GPO and enters the offices of the Freeman’s Journal to place an advertisement for the tea merchant Alexander Keyes. In the adjacent offices of the Evening Telegraph, Stephen Dedalus tries to persuade the editor Myles Crawford to publish a letter about bovine foot and mouth disease by the schoolmaster Garrett Deasy. The building fell victim to the destruction visited on the area in 1916 but we can still recall the wealth of Homeric themes and symbols–and for this former journalist the ambiance of an old-fashioned newspaper office– with which Joyce endowed the chapter.

The characters in Aeolus leave the newspaper by its exit on Middle Abbey Street. No visit to literary Dublin is complete without attending a performance at the Abbey Theatre, founded by Lady Gregory and W. B. Yeats in Lower Abbey Street on the other side of O’Connell. But that is an evening’s pleasure and at this point we will follow Leopold Bloom into O’Connell Street heading toward the bridge over the Liffey. We are in the Lestrygonians episode at 1:10 P.M.

Pineapple rock, lemon platt, butter scotch. A sugarsticky girl shovelling scoopfuls of creams for a christian brother. Some school treat. Bad for their tummies. Lozenge and comfit manufacturer to His Majesty the King. God. Save. Our. Sitting on his throne sucking red jububes white.

A sombre Y.M.C.A. man, watchful among the warm sweet fumes of Graham Lemon’s, placed a throwaway in a hand of Mr. Bloom.[U 124/1]

The sign “the Confectioner’s Hall” still hangs over the store which housed Lemon’s sweetshop. Along this stretch of the boulevard a few postboxes of the British imperial era survive with the royal seal implanted on the red ground.

The hugecloaked Liberator’s form__ the monument to Daniel O’Connell, the father of Catholic emancipation in 1829 __ which Bloom had passed earlier in the morning in the Dignam funeral procession punctuates the end of the boulevard. Bloom looks to the right along Bachelor’s Walk, a Liffeyside quay. He spots Stephen’s sister Dilly Dedalus outside Dillon’s auction house and surmises she has been trying to sell family possessions to keep the household afloat. “Good Lord, that poor child’s dress is in flitters. Underfed she looks too. Potatoes and marge, marge and potatoes. It’s after they feel it.” [U 124/41] In the next chapter Wandering Rocks she will corner her ne’er-do-well father Simon Dedalus and extract a shilling from him. The scenes evoke the cruel reality of the Joyce family’s descent into destitution after their father squandered his inheritance.

Crossing the O’Connell Bridge Bloom looks down at the traffic on the muddy Liffey. Barges from the Guinness Brewery, still a potent presence in the city, and gulls “flapping strongly, wheeling between the gaunt quaywalls.” He looks ahead to the Ballast Office at the corner of Aston Quay and its famous clock set to 25 minutes behind Greenwich time which was Irish time before 1914. The building has been reconstructed and its clock, set ahead and moved to where it is no longer visible from this spot.

We are on the south bank of the city, on Westmoreland Street, one of its more bustling crossroads.

Hot mockturtle vapor and steam of newbaked jampuffs rolypoly poured out of Harrison’s. The heavy noonreek tickled the top of Mr. Bloom’s gullet. [U 129/232]

In front of the restaurant, which is still in operation, Bloom chats with Mrs. Josie Breen. Further ahead on the other side of the street he remarks on the imposing curved facade of the Bank of Ireland.

Before the huge high door of the Irish house of Parliament a flock of pigeons flew. Their little frolic after meals. Who will we do it on? I pick the fellow in black.

Two hundred years ago in the Georgian era the building housed the Irish Parliament. Its former chambers are open to the public during banking hours. In Portrait Stephen Dedalus goes to the Bank of Ireland to cash in prizes he won as a student at Belvedere so that he can shower his impoverished family with food, theater tickets and gifts. [PA Chapter 2]

Across Westmoreland Street from the bank at the beginning of College Street is the commanding statue of the poet Thomas Moore. He [Bloom] crossed under Tommy Moore’s roguish finger. They did it right to put him up over a urinal; meeting of the waters. Ought to be places for women. Running into cakeshops. Settle my hat straight. [U 133/414] The statue of the author of The Meeting of the Waters, situated next to a men’s toilet, inspired a chronic Dublin joke.

Behind Moore looms the campus of Trinity College. Ireland’s distinguished institution of higher learning was established by Queen Elizabeth I in 1592 and over the centuries educated the likes of Jonathan Swift, Oliver Goldsmith, Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett. Although Bloom probably never set foot inside the gates (Catholics were forbidden by their bishops to attend until fairly recent times) it’s worth a Joycean digression to do so, at the very least to see the Book of Kells, the 9th century illuminated manuscript of the Gospels in the Library.

Dodging traffic on College Green, one of the most frenetic of Dublin’s hubs (in Joyce’s time a tram intersection), follow Bloom around the periphery of the College along Nassau Street, the boundary of the fashionable commercial quarter. It includes several bookstores with Irish inventory. [Fred Hanna on Nassau Street; Waterstone’s in Dawson Street and Greene’s Bookshop, Ltd. in Clare Street.] On June 10, 1904, Joyce encountered an auburn-haired young woman walking on Nassau Street and asked her for a date four evenings later. Nora Barnacle was working at Finn’s Hotel at the corner of Clare Street. The rooming house long since ceased operation but when the leaves are off the trees on the College playing fields its name can be discerned on the side wall of the building.

We will peel off from Nassau Street at this point.

Grafton Street gay with awnings lured his senses. Muslin prints, silkdames and dowagers, jingle of harnesses, hoofthuds lowringing in the baking causeway. [U 137/614]

Grafton Street, now a pedestrian mall, is still Dublin’s foremost shopping center. He passed, dallying, the windows of Brown Thomas, silk mercers. Cascades of ribbons. Flimsy China silks. Bloom considers buying a pincushion for Molly at Brown Thomas, still a possibility today.

Bewley’s Oriental Cafe at Number 10 Grafton Street is one of a chain of century-old coffee houses in which Joyce and his friends gathered to talk. Its popularity and the quality of its moderately priced fare endure.

We turn left into Duke Street with Bloom so that we can order the very same lunch at Davy Byrne’s “the moral pub” at Number 21. The gorgonzola sandwich and a glass of Burgundy wine remain on the menu after nine decades, the cheese still deliciously biting on strips of Irish brown bread.”

…fresh clean bread, with relish of disgust pungent mustard, the feety savour of green cheese. Sips of his wine soothed his palate. Not logwood that… [U 142/818]

Bloom leaves the pub and turns right toward Dawson Street, follows a blind man into Molesworth Street until Kildare Street where he catches sight of Blazes Boylan. To avoid meeting his wife’s lover Bloom swerves right toward the National Museum. No Dublin tourist should miss its collection of Celtic antiquities.

After inspecting ancient Greek statues on the ground floor, Bloom proceeds to the neighboring institution on Kildare Street, the National Library of Ireland. This is the setting for the Scylla and Charybdis chapter in which Stephen Dedalus expounds his theory about Shakespeare and Hamlet to a group of Dublin intellectuals. At the head of the stairs is a monument to T. William Lyster, the Quaker (or in Joyce punctuation quaker) librarian who presides over the session. To the right are the reading room and the librarian’s office in which Stephen holds forth. [U 154/142]

Leaving the National Library, turn left and proceed to the end of Kildare Street. The entrance to the Shelbourne, Dublin’s grande dame hotel opened in 1867, faces the north side of St. Stephen’s Green, one of Europe’s loveliest parks.

But the trees in Stephen’s Green were fragrant of rain and the rainsodden earth gave forth its mortal odour, a faint incense rising upward through the mould from many hearts. The soul of the gallant venal city which his elders had told him of had shrunk with in a moment when he entered the sombre college he would be conscious of a corruption other than that of Buck Egan and Burnchapel Whaley. [PA chapter 5]

Stroll through the Green to its south side and notice the bust of James Joyce just beyond the bandstand where concerts are given at lunchtime in summer. “The sombre college” is Newman House of University College Dublin (alma mater of Joyce and of Stephen Dedalus) which occupies a pair of noble Palladian buildings at Numbers 85/86 St.Stephen’s Green South. Constructed in the mid-1700’s as private residences, they were taken over a century later by the first Catholic university established in Ireland. John Henry Cardinal Newman served as rector. One can visit the spartan room in which Gerard Manley Hopkins, the Jesuit poet and scholar lived as well as the Physics Theatre in which the dean of studies challenges Stephen Dedalus’s views on aesthetics and Stephen attends a deadly science class. The Commons Restaurant in the basement has a Michelin star and a celebrity clientele.

Walk around to the east side of the Green bearing right into Merrion Row and Merrion Street until we reach another enchanting oasis framed by Georgian houses, Merrion Square. The house at Number 1 belonged to Sir William Wilde, the physician father of Oscar. Joyce chose the spot for his first date with Nora Barnacle on June 14; she stood him up.

Follow along the north side of the square to Holles Street and the National Maternity Hospital, setting for the Oxen of the Sun chapter of Ulysses in which Bloom visits Mrs. Purefoy while Stephen Dedalus drinks and philosophizes as he awaits Buck Mulligan.

Returning to Merrion Square, look at other houses with famous former residents such as Daniel O’Connell’s at Number 58, W. B. Yeats’s at Numbers 52 and 82. George Russell (A.E.), editor of the Irish Homestead and one of the real life characters who make an appearance in Ulysses, had his office at Number 84.

EXCURSION 4:

Eumaeus, Sirens, Wandering Rocks, Cyclops

Discussing these and kindred topics they made a beeline across the back of the Customhouse and passed under the Loop Line bridge where a brazier of coke burning in front of a sentrybox or something like one attracted their rather lagging footsteps. [U503/100]

It is 12:40 A.M. and Leopold Bloom, in the hope of sobering up Stephen Dedalus after their wild evening in Nighttown is trying to lead the younger man to the cabman’s shelter on Custom House Quay.

I am proposing a walk focused on the River Liffey which we will criss-cross from the north bank to the south and in the process recall not only James Joyce’s writings but highlights from Dublin’s earlier history that shaped his mindset. We should begin, therefore, at the city’s proudest public building, the Custom House situated two quays east of O’Connell Bridge.

It took a decade beginning in 1781 to construct this imposing structure of of Portland stone and granite. James Gandon was the architect. Harps are etched into the capitals of the front columns. A copper dome with four clocks surmounted by a 16-foot statue of Hope resting on an anchor gives it a soaring quality particularly when the illuminated building is viewed at night from the opposite bank of the Liffey.

In this penultimate episode Eumaeus, Bloom is bound for his home on Eccles Street, but since we we have already covered this territory in Excursion 2 we will head in the opposite direction. Walking west past O’Connell Bridge we cross the river by the Halfpenny Bridge to Wellington Quay on the south bank and go under the Merchants’ Arch.

We have plunged into the Temple Bar area, one that has been transformed in the 1990’s from derelict to super-trendy. Joyce would be amused by its current reputation as Dublin’s Left Bank, a homing ground for rock ‘n’ roll royalty and celebrities from the film, art and fashion colonies of Europe and the United States. In Joyce’s time, the narrow cobblestone streets and crooked lanes were dotted with second-hand bookstores, some of which still survive. In the earlier episode Wandering Rocks, Bloom buys a copy of Sweets of Sin [U 194/610] for Molly from a bookseller under Merchants’ Arch while in nearby Bedford Row Stephen is scanning the slanted bookcarts. [U 199/836] “I might find here one of my pawned schoolprizes”. In this poignant scene, he meets his sister Dilly who has just paid a penny for a tattered French primer.

__What did you buy that for? he asked. To learn French? She nodded, reddening and closing tight her lips…

__Here, Stephen said. It’s all right. Mind Maggy doesn’t pawn it on you. I suppose all my books are gone.

__Some, Dilly said. We had to.

She is drowning. Agenbite. Save her. Agenbite. All against us. She will drown me with her, eyes and hair. Lank coils of seaweed hair around me, my heart, my soul. Salt green death.

We.

Agenbite of inwit. Inwit’s agenbite.

Misery! Misery!

Let us trace Bloom’s footsteps as he strides along Wellington Quay, Sweets of Sin in his pocket, and crosses Grattan Bridge (formerly Essex) to the north bank of the Liffey. Yes, Mr. Bloom crossed bridge of Yessex. To Martha I must write. Buy paper. Daly’s.

The stationery store on Ormond Quay Upper is gone but Bloom’s destination, the Ormond Hotel at Number 8, is where at 4 P.M. on a Bloomsday Joyceans invariably congregate. This is the setting for the Sirens episode, the musical chapter of Ulysses, which begins with an overture as a viceregal procession passes by.

*Bronze by gold heard the hoofirons, steelyringing.

Imperthnthn thnthnthn.

Chips, picking chips off rocky thumbnail, chips.

Horrid! And gold flushed more.

A husky fifenote blew.

Blew.Blue bloom is on the.

Goldpinnacled hair.

….[U 210/1]

The Ormond has undergone several refurbishings over the century but it is still just dreary enough to permit a re-enactment of the episode in which Leopold Bloom, Simon Dedalus, Blazes Boylan and several other characters from previous chapters converge to chatter and listen to songs. In the bar which is still at the right of the entrance Boylan orders a sloegin to drink before setting off for his rendez-vous with Molly. On the left, rechristened “the Siren Suite”, is the dining room in which Bloom sups on liver, “mashed mashed potatoes” and cider while he broods over what must be transpiring in his bedroom on Eccles Street.

In strict chronological order we would move along to the Cyclops chapter, Joyce’s satirical take on Irish nationalism and bigotry, in which a citizen and his dog harass Bloom. The episode unfolds in Barney Kiernan’s pub at Number 9 New Britain Street, a short distance from the Ormond Hotel up Arran Street. The actual pub, a hangout for a clientele drawn from the Four Courts, no longer exists so we might as well survey the law complex from Inns Quay adjacent to the Ormond. Aso designed by James Gandon, and a frequent point of reference in Joyce’s writing, the Four Courts were destroyed during the Irish Civil War in 1922 and scrupulously reconstructed.

Back across the Liffey we go via Richmond Bridge to Merchants’ Quay. At the corner of Winetavern Street is the Church of St. Francis of Assisi, known to Dubliners as Adam and Eve’s. Born as an underground church in the 17th century when Catholic worship was severely repressed in Ireland, its nickname derives from a nearby tavern of that era.

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.[FW 1]

In the opening lines of Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s reversal of the nickname, according to scholars, signals that further games will be played with language and with concepts of time and space.

Miss Julia Morkan, one of the hospitable sisters in the Dubliners story The Dead, is the leading soprano in the choir of Adam and Eve’s. “The dark, gaunt house” in which the women conduct their genteel lives is two quays beyond at 15 Usher’s Island. According to Richard Ellmann, the Morkan ladies were modeled after Joyce’s great-aunts who ran a music school from their home at that address and gave an annual Christmas party. Joyce’s father, like Gabriel Conroy in the story, carved the goose and made a speech. Though much the worse for wear including fire damage to its roof, the house still maintains its elegant Georgian facade and the rooms on the first floor in which the party takes place are intact. John Huston used the exterior for the filming of The Dead in 1987.